Ecofeminism and Urban Flooding in Chicago

Ecofeminism & Green Spaces in Chicago (1) Heading link

In Chicago, there is a deeply inequitable distribution of and access to green infrastructures, considerably in communities of color. This is reflected within the division of North and South Chicago and access to parks and green spaces that also highlight the broader class and racial divides within the city. A specific and guiding consequence of the decision-making of the inequitable green space distribution is urban flooding in Chicago [1]. In the early 2000s, Mayor Richard M. Daley promised to make Chicago one of the greenest cities in America, and under its 2008 climate plan, the city of Chicago was to have 6,000 green rooftops by 2020 [2]. With this ambitious goal in mind, there must also be a similar conversation on the disproportionate access to all green spaces across Chicago. With tenets of environmental justice in mind, gender, racial and social implications must guide these conversations and, ultimately, ecofeminism must have a permanent place within urban landscapes.

Community gardens and parks make a significant and dramatic impact on improving the quality of life for communities. Research shows a direct pathway between green space and improved mental health, reduced risk of chronic diseases, and stronger social cohesion [3]. However, discussions of green infrastructure around Chicago continue to overlook the critical linkage between access and the implications of this missing infrastructure. The Friends of the Park report listed 16 areas where residents don’t have such access, all of which are concentrated in the South and West sides of the city–typically lower income neighborhoods with residents of color [4]. Residents with higher levels of education and income are more likely to have access to parks and green spaces [5]. Green infrastructure, such as green roofs, rain gardens, urban gardens, and parks, are also often used in urban environments to reduce stormwater runoff that could otherwise lead to flooding. Chicago has few detention pods and only 8.5% of the city’s acreage dedicated to parks [6].

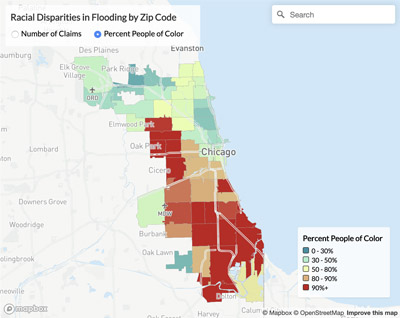

Institutional, residential, and city buildings and spaces are now using green infrastructure to lessen the effects of large storm events. I decided to look at green infrastructure including city parks, community rain gardens, and green rooftops. There is a clear disproportionate impact of urban flooding in communities of color [7]. Smaller stormwater infrastructure elements such as rain gardens, green roofs, and parks can improve community flood resilience by reducing the burden on overflowed sewer systems [8]. However, green infrastructure solutions alone may not be enough to significantly reduce urban flood. That, along with other community engagement solutions such as home protections solutions, may also effectively mitigate flooding.

Ecofeminism & Green Spaces in Chicago (2) Heading link

In the United States, flooding is the most common type of natural disaster, with federal insurance claims averaging $1.9 billion annually, according to a 2017 report by the Pew Charitable Trusts [9]. Metropolitan Chicago is predicted to experience more frequent and worsened rainfall due to climate change [10]. Weather forecast models are predicting these harder and more frequent downpours will inevitably overwhelm stormwater systems that were built long ago and may no longer have the infrastructure to support these changes. Urbanization in Chicago has led to more development and a decrease in impervious surfaces and rainwater detention areas [11]. This urbanization, combined with climate change, a more extreme water cycle, and higher magnitude storms, has led to many intense flooding events [12]. The city has been working on better land use policies and site planning for water engineering in order to improve environmental and economic standards.

Certain areas of Illinois and Chicago experience greater amounts of flood occurrences and are more susceptible to floods. Typically, these areas have outdated stormwater management systems and have not been updated as floodplains, or they have experienced increased development [13]. Increased development leads to increased stormwater and flooding downstream once the drainage systems are overwhelmed. The majority of Chicago was developed without stormwater management in mind [14]. Natural drainage was completely overlooked in early construction of the city, with little to no infiltration or evapotranspiration areas. Floodplains were mapped out nationally in the late 1960s and now should be expanded due to development and increasing precipitation rates [15]. Areas that experience urban flooding downstream are typically low-income communities of color. These areas become less economically, socially, and environmentally sustainable to live and work in. According to the Center for Neighborhood Technology, 87 percent of flood damage insurance claims between 2016 and 2017 were paid to communities of color, much of which are located in Chicago’s south suburbs [16]. Flooding and flood insurance are costly, redevelopment is less likely, disinvestment goes up, properties lose value, and pollutants reduce water quality.

Ecofeminism quote Heading link

Urban gardens inherently follow ecofeminist ideologies; they extend Western women’s traditional role and knowledge from the domestic sphere and into broader communities, deconstructing social dynamics as they are often led by community and not imposed by those in power, build community engagement, and create interconnectivity between human, earth, and other living beings.

Ecofeminism & Green Spaces in Chicago (3) Heading link

Green roofs, rain gardens, urban gardens, and parks are used in urban environments to reduce stormwater runoff that could otherwise lead to flooding, and many local and community urban gardeners in urban environments are working to address this themselves. The documentary Urban Garden by Jay Sokolvsky details the conditions that led to the urban gardening movement in New York in the 1970s [17]. Over 20,000 vacant lots, many used as dumping grounds, became repurposed and transformed into community gardens with the leadership of Liz Christy and “Green Guerillas.” In 2000, Operation Green Thumb, under NYC’s Parks and Recreation department, began to oversee community gardens in partnership with urban gardening organizations and communities as a continuation of this work [18]. Many ecofeminist activists and organizers have expanded on Christy’s work to use urban gardens as an effective tool to address wider issues related to the urban environment. This work also challenges some of the most complex justice issues faced in urban spaces, including Chicago, such as access to fresh, healthy, and affordable produce; climate change; food insecurity; and health and wellness. Urban gardens inherently follow ecofeminist ideologies; they extend Western women’s traditional role and knowledge from the domestic sphere and into broader communities, deconstructing social dynamics as they are often led by community and not imposed by those in power, build community engagement, and create interconnectivity between human, earth, and other living beings.

The intersection of urban challenges, such as urban flooding, requires a wider and deeply embedded commitment to community efforts such as community gardens and other community-led initiatives that address justice issues. Conversations around addressing the inequitable distribution of green spaces must also centralize social factors such as race and gender.

About the Author Heading link

Jazmin Vega is a graduate assistant at the Women’s Leadership and Resource Center and a second-year graduate student in UIC’s Urban Planning and Policy program. She received a Bachelor of Arts (BA) in political science and a BA in women’s studies from Metropolitan State University of Denver. During her undergraduate experience, Jazmin worked as a peer mentor with students learning how to navigate higher education. In that work, she centered students’ struggles to find and connect to valuable campus resources and building space for first-generation students of color. She is deeply committed to her communities and doing work that matters.

Citations Heading link

- [1] “Chicago City Hall,” Greenroofs.com, last updated March 12, 2019, accessed August 2020, https://www.greenroofs.com/projects/chicago-city-hall/.

- [2] See note 1 for reference

- [3] Viniece Jennings and Omoshalewa Bamkole, “The Relationship between Social Cohesion and Urban Green Space: An Avenue for Health Promotion,” International journal of environmental research and public health (MDPI, February 4, 2019), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6388234/.

- [4] “State of the Parks 2018” (Chicago, IL: Friends of the Park, 2018), pp. 11-67.

- [5] See note 4 for reference

- [6] Martin Jacobson, “Chicago Green Roofs,” World Wildlife Foundation, originally published March 1, 2012, accessed August, 2020, https://wwf.panda.org/?204400/Chicago.

- [7] Peter Hass, Preeti Shankar, and Marcella Bondie Keenan, “Assessing disparities of urban flood risk for households of color in Chicago,” Illinois Municipal Policy Journal 4, no. 1 (2019).

- [8] See note 6 for reference

- [9] Laura Lightbody, “Flooding Disasters Cost Billions in 2016,” The Pew Charitable Trusts, 2017, https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/articles/2017/02/01/flooding-disasters-cost-billions-in-2016.

- [10] See note 6 for reference

- [11] See note 6 for reference

- [12] Linda Velazquez, “New York Passes Mandatory Green Roof Legislation,” Greenroofs.com, originally published April 18, 2019, accessed July, 2020 https://www.greenroofs.com/2019/04/18/april-18-2019-new-york-passes- mandatory-green-roof-legislation/

- [13] Laura Lightbody, “Flooding Disasters Cost Billions in 2016,” The Pew Charitable Trusts, 2017, https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/articles/2017/02/01/flooding-disasters-cost-billions-in-2016.

- [14] See note 7 for reference

- [15] See note 13 for reference

- [16] See note 7 for reference

- [17] Emily Benton Hite et al., “Intersecting Race, Space, and Place through Community Gardens,” Annals of Anthropological Practice, 2017, https://www.academia.edu/35213999/Intersecting_Race_Space_and_Place_through_Community_Gardens.

- [18] See note 17 for reference